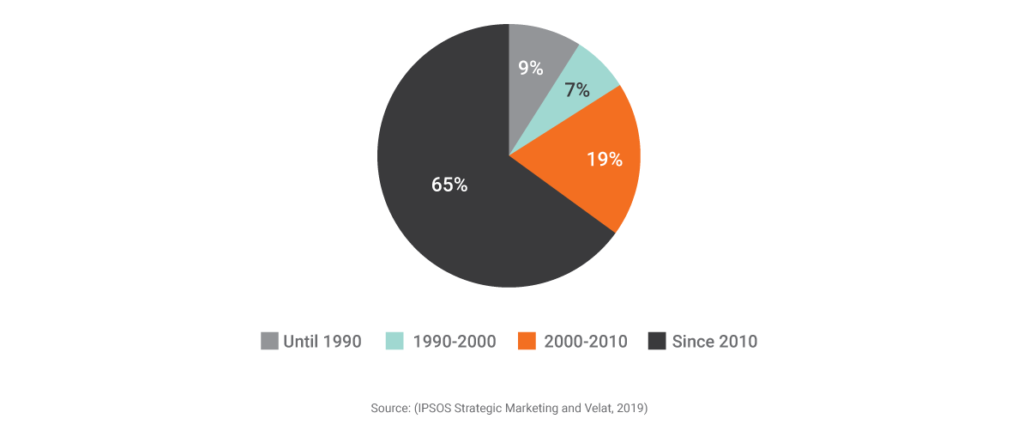

The association of citizens and their involvement in decision-making and policy-making in Serbia is relatively favorably regulated by law, despite certain shortcomings. The key status laws that enable more favorable establishment and operation of citizens’ associations were adopted at the beginning of the analyzed period, i.e. 2009-2010. After the adoption of these laws, the number of established citizens’ associations grew. According to the data of the Business Registers Agency, 34,093 associations and 927 endowments and foundations are officially registered in Serbia. The largest number of these organizations, as many as 2/3, were founded after 2010, that is after the adoption of the Law on Associations.

Despite this, in practice we mostly see disinterested, passive and obedient citizens who rarely engage in civic activism. On the other hand, in the last few years there has been an expansion of social movements and civic initiatives that bring critical voices within civil society and provide hope for the possibility for development of the necessary pluralism.

On one hand there is a relatively democratic legal framework for citizens’ associations that encourages action in civil society. On the other hand, the analysis shows that limited financial resources and the state policy of control, conditioning and holding the interests of the ruling parties above all else significantly channel the activities of organizations and essentially restrict the freedom of association.

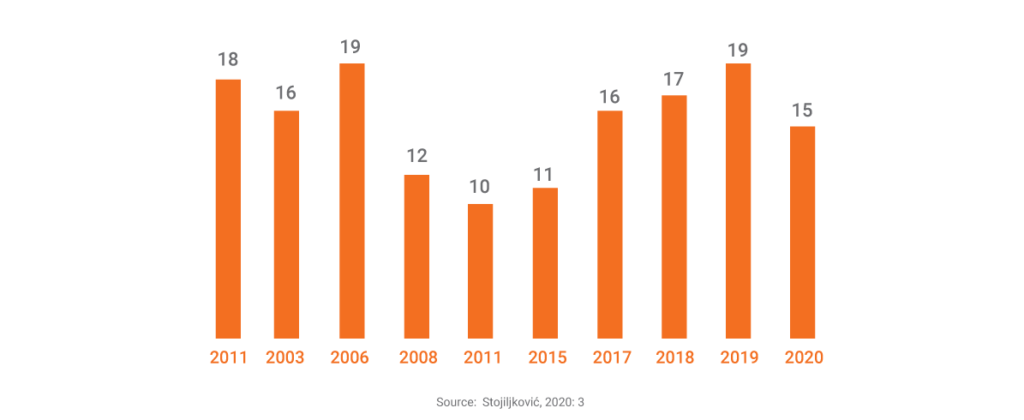

The activities of civil society in Serbia are largely determined by the changes after October 5th, the democratic transition and the support and direction of international donors in the first years after 2000. Regarding the democratic environment for civil society in Serbia, two trends can be seen in the analyzed period. The first is the trend of easing the formal conditions for the organization and operation of civil society organizations from 2009 to 2012 and the consequent increase in the number of registered associations. In this period, the most influential and most visible part of civil society are non-governmental organizations that strive to cooperate with the state, limit its power and provide replacements for many state functions, especially in the field of social protection.

The second trend has been evident since 2014, when due to the collapse of democracy, the opportunities for free and independent action of civil society organizations decreased. This applies in particular to civil society activities related to monitoring the work of public institutions and advocating for public policies. During this period, new social movements and civic initiatives that were critical of the authorities and the way politics was conducted in the country began to emerge (again).

In reality, civil society has very little influence on creating policies and regulations. Formal mechanisms aimed at involving the civil society in those processes merely feign democracy, instead of improving communication and cooperation. The government can’t take criticism and conducts smear campaigns against civil society actors that in any way try to stand up to its authoritarian tendencies, or advocate for human rights and democratic governing. Simultaneously, the governing parties go out of their way to create their own NGOs for the purpose of abusing the means from the state budget allocated for the civil society, as well as invalidating critics and faking public support.

More over, a critical look at the civil society organizations (CSO) reveals that they are not open enough and lack in communication with citizens. Many CSOs don’t have a clear idea whose interests or views they represent, nor do they show a need to change their approach to communication with citizens. Numerous studies have shown that citizens do not believe that these organizations have the power, capacity or desire to actually influence the resolving of issues important to citizens.