As stipulated by the Constitution, the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia is the highest representative body and the holder of legislative power. The National Assembly is also in charge of monitoring the executive branch. In practice, citizens’ interest in the parliament is declining, and the lack of trust in the National Assembly is associated with a collapse of confidence in democracy. The centralization of power, one-sided narratives widespread in public space and domineering the media as a whole contribute to the portrayal of the President of the Republic as the only authority in charge of all issues and topics, regardless of the constitutional system. This significantly degrades the position of the parliament. In addition to the centralization of power in the hands of the executive, the Parliament faces a number of structural weaknesses and poor internal practices.

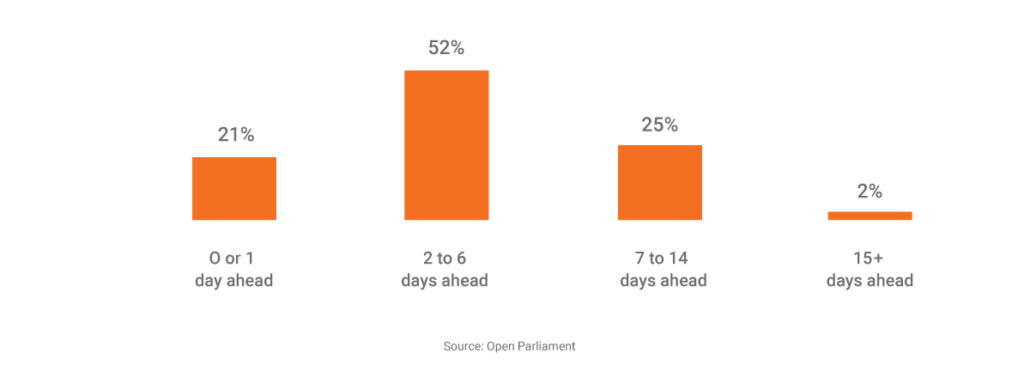

When it comes to the legislative function, during the last decade, laws would most often “speed” through the Assembly, without significant involvement of MPs and with frequent and unjustified recourse to urgent procedures. Committees and plenary sessions were often hastily agreed upon, with the agenda of the plenary sessions being announced at the last minute, leaving MPs little time to prepare for the debate on the acts that are to be on the agenda and to draft amendments. In the absence of the annual work plan of the National Assembly, the problem of quality preparation of MPs for work is even clearer.

From 2005 to 2010, the Government proposed on average about 62% of laws and other acts, and from 2016 to 2020, that share increased to as much as 97% of all adopted laws. This growth is a consequence of the practice of overlooking law proposals made by opposition MPs when creating an agenda for the plenary session. So, although the MPs from the opposition have the right by the letter of the law to initiate and change the laws, in practice they failed. In addition, the ruling majority used various obstructive practices (filibustering), such as submitting numerous amendments to laws lacking truly relevant content in order to limit the time for opposition MPs to speak. This trivialized the parliamentary debate itself.

The monitoring role of the parliament is most often realized through the work of the committees and through parliamentary questions.

In practice, the actual power of the National Assembly committees is limited by the will of the ruling majority, as well as the capacities and resources of their members and staff, which often do not match the government’s. The structure of a committee in the Serbian Assembly reflects the composition of the Parliament, proportionally representing the parliamentary groups in relation to the total number of committee members. Unlike the fine practice that was in place in the first decade of 2000, the distribution of seats in parliamentary committees between the majority and the opposition was changed to the detriment of opposition MPs. Finally, the functioning of parliamentary committees is in most cases characterized by a general lack of efficiency. Committee members do their jobs formally and hastily, instead of a fundamental approach to the topics that are on the agenda.

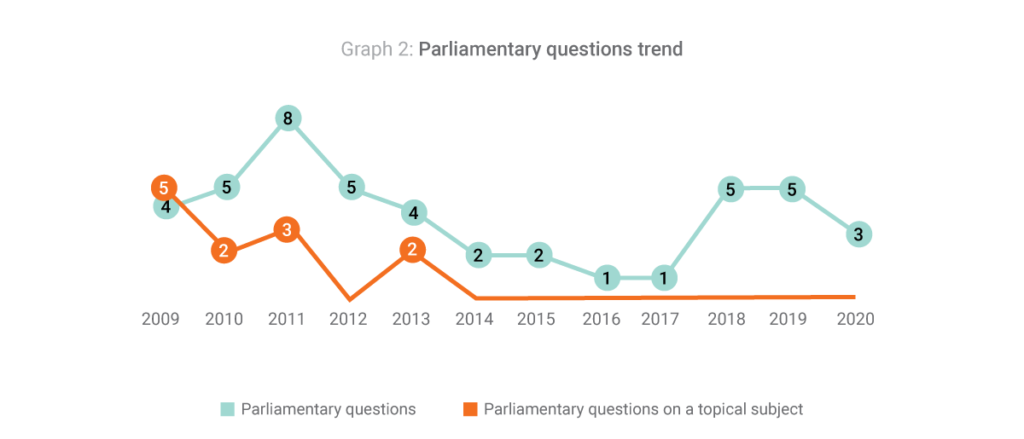

Parliamentary questions, in oral or written form, obligate the representative of the Government to answer. Although the use of this mechanism has increased compared to 2018, in practice, asking questions does not significantly contribute to the quality of Parliament’s monitoring function. The second type of parliamentary questions are those that relate to the current topic. In the last seven years, they have been completely neglected in practice.

In Serbia, a tradition of holding a public hearing before adoption of systemic acts does not exist. Nonetheless, when speaking about public hearings it’s important to note that them being regularly held is not enough for it to be a true contribution to the monitoring role of the parliament. What is crucial is that parliamentary committees actually take the findings from these hearings seriously and follow them through. The format of the conclusions adopted after a public hearing is also of great importance.

Commissions and committees of inquiry, as the next monitoring mechanisms initiated by committees, are used even less frequently in practice. Intended as ad hoc bodies, they allow the Parliament to establish facts on certain matters of public interest or important events or aspects of the work of the executive. In practice, these mechanisms yielded no concrete results.

Despite a solid constitutional system stipulating a strong legislature, the position and influence of parliament over the past decade has been hindered by the prevailing centralization of power in the hands of the executive, making it largely dependent on government decisions, especially the President. In addition, as a result of the increasing abuse of mechanisms and obstructions, the Assembly has become a mere façade instead of a temple of democracy, which is a role assigned to it by the legislative framework.